(Republished from March 2014)

When a franchise achieves as much success as the Lakers have over the past 40 years, it’s almost assumed that critics and envious fan bases will try to tear them down. Since they don’t have the ability to erase those accomplishments from the history books, they instead try to either distort or discredit them. These are the same people who believe that anything good that happens to the Lakers is the result of cheating, but never investigate the possibility of anything fishy going on when they lose.

Their newest strategy is what I like to call “Preemptive Delegitimization.” These are the guys who have already declared the Lakers the winners of the 2014 NBA Draft Lottery. You can’t help but be impressed. If the Lakers do win the lottery, they’ll say it was fixed. If they get the second pick, they’ll say it’s because the NBA knew it would look too fishy to give them the first pick. If the player the Lakers draft ends up leading them to a championship, then it will be because Adam Silver rigged it for them. If the Lakers end up getting a pick that’s worse than where they would have picked if the draft was based on won-loss records, you won’t hear a single peep.

Conspiracy theories are nothing new in sports. With each major scandal, whether it’s Pete Rose, Tim Donaghy, Connie Hawkins, or Paul Hornung, the shadow of doubt has gotten wider. In cases where human error is involved, it is now commonplace to question whether or not the mistake was really unintentional or if there’s something more clandestine behind it. In the cases where Goliath beats David, the popular thing to do now is to repeat the conspiracy theory over and over until it sheds the conspiracy tag altogether and becomes an outright fact.

Perhaps nothing has helped to fuel this habit more than the Internet. We’ve never had more tools at our disposal for rewriting history. With just a few clicks, anyone can find a stat to help support whichever point he or she is trying to make. Even the least tech-savvy among us, with just minimal editing skills, can put together a YouTube video that would make Leni Riefenstahl envious.

I was reminded of this the other day when one of the most often repeated conspiracy theories of the past 20 years came across my Twitter feed. Alex Kennedy of BasketballInsiders.com tweeted out a story by his colleague Jabari Davis about Australian NBA hopeful Dante Exum:

Dante Exum says the L.A. Lakers are "the best option" for him. Could he force his way to L.A. like Kobe Bryant did? http://t.co/oVgG8qDqfN

— Alex Kennedy (@AlexKennedyNBA) February 4, 2014

It’s important that I mention that Jabari has no agenda. Not only is he from Los Angeles but at one-time was a contributor to this very site. If you were to read his story, you’d see that Jabari does use words like “rumor” and “paralleling stories” when discussing the events surrounding how Kobe ended up on the Lakers. But that’s very different than what the headline of the story implies. The headline states it as fact, further giving both life and legitimacy to a rumor. Just look at one of the first replies Kennedy received to his tweet:

https://twitter.com/esjaygee/status/430545296758931456

What really happened and what’s reported to have happened are distinctly different. Looking back on how we got here could serve as an excellent case study in how rumors evolve into facts in the digital age. Those who are fans of Kobe would tell you that the rumor is 100 percent false. Those who despise either Kobe or the Lakers will tell you that Kobe, his dad, and his agent basically threw on ski masks, locked the doors to the Continental Airlines Arena, and pointed their guns at the heads of the 29 GMs to ensure that Kobe would be a Laker.

As is the case with most legends, the truth lies somewhere in the middle.

Shaq and Vlade

Perhaps one of the worst-kept secrets was that the Lakers were planning to pursue Shaquille O’Neal in the Summer of 1996. In order to make Shaq a competitive offer, GM Jerry West needed to create enough cap space to be able to compete with the offer the Orlando Magic would make to retain the top pick from the 1992 NBA Draft.

West had spent every year between Magic Johnson‘s HIV announcement in 1991 and 1996 rebuilding a roster that was not only good enough to win 53 games but with one of the youngest and most entertaining teams in the league. To clear enough cap space to make a run at Shaq, West risked blowing up that team and ending up with nothing. He let free agents like Sedale Threatt leave without any compensation and traded former first-round picks like Anthony Peeler and George Lynch for nothing but second-round picks.

Divac, the Laker’s highest-paid player at the time, needed to be moved, not just to free up a sizable chunk of cap space but because the two of them played the same position. If they could trade Divac for a first-round pick, then they could not only free up cap space but could use the pick to draft a young player with upside who wouldn’t be eligible for a significant pay increase for four years.

In hindsight, it seems like a crazy trade, but there wasn’t anybody at the time who thought to trade the 13th pick in the draft for a proven center like Divac was either crazy or stupid. That’s just one bit of revisionist history that’s changed over time. As Kobe’s ascension to basketball immortality coincided with the demise and ultimate relocation of the Hornets, it became harder and harder for people to accept that any team would ever trade Kobe Bryant for Vlade Divac by choice.

Instead of relying on hard evidence, it has become popular to intentionally confuse facts with hindsight and pretend all of us knew that Kobe would not only be a Hall of Famer but that it happened on the Lakers because Kobe refused to play for any other team. Did we really expect them to pass up the chance to feed both the “Kobe is a selfish prima donna” narrative and the “Lakers only win because they cheat” narrative at the same time?

The truth is that it is rarely ever mentioned why the Hornets would consider trading the 13th pick for Vlade Divac. A year before the trade, the Hornets traded Alonzo Mourning after they had failed to reach an agreement with him on a contract extension. With 42-year-old Robert Parrish and Matt Geiger replacing Mourning in the starting lineup, they went from a 50-win playoff team to a 41-win lottery team.

In a 2008 article in the Winston-Salem Journal, John Delong reported that Hornets’ VP Bob Bass was set on acquiring a center that summer and felt that the best they could do in the draft was either Todd Fuller or Vitaly Potapenko. When the chance to trade the 13th pick for Divac presented itself, according to Delong, they “jumped at the chance.” Here’s what he wrote:

“When you look back at it when we made that trade, here was a 17-year-old kid who had played in high school,” said Bob Bass, the Hornets’ executive vice president of basketball operations at the time. “Twelve other teams passed on him. We made a decision to win now and not later. We had Dave Cowens as our first-year coach, and I wanted to give him a chance to win. I knew if we got Divac in here, we’d win. I didn’t feel the same about Bryant. Without Divac, I thought we might have won 25 games.”

I actually feel bad for the way in which Divac’s legacy has been diminished in order to fit a false narrative. He was much better than just an average center. He was 28 at the time of the trade and had just completed his seventh season. He was owed $4.7 million in the first of two remaining years left on his contract. He’d never made an All-Star team but that had more to do with him playing in the same conference as Hakeem Olajuwon, David Robinson, and Dikembe Mutombo.

What’s also never mentioned is how much success the Hornets had with Divac on their roster. In his first season in Charlotte, they won a franchise-best 54 games. The following year, they won 51 games and a playoff series. Fuller and Potapenko, the two centers the Hornets had considered drafting, were drafted with the two picks before it was time for the Hornets to pick.

The Lakers’ desire to create cap space and the Hornets need for a center just weren’t salacious enough for conspiracy theorists. They needed something they could sink their teeth in. The truth is that the Hornet’s involvement in Kobe ending up on the Lakers pretty much ended when they got their center. As much as history has been distorted, the real reason why Kobe Bryant wasn’t a Hornet was that the Hornets didn’t want Kobe Bryant, not the other way around. Since that story wasn’t good enough for them, one had to be embellished.

While there was some backroom scheming involved in the Lakers getting Kobe, none of it involved the Hornets or Kobe’s reluctance to play in a small market. What really happened was neither scandalous nor even revelatory — just a small bit of gamesmanship with enough ambiguity to let it snowball into what we think we know about what happened.

Kobe and the Nets

In order for the Lakers to get Kobe, two important things needed to happen. First, they needed to acquire a lottery pick. Second, Kobe had to still be available when it came time for that selection. The Hornets could accommodate their first need, but couldn’t guarantee the other.

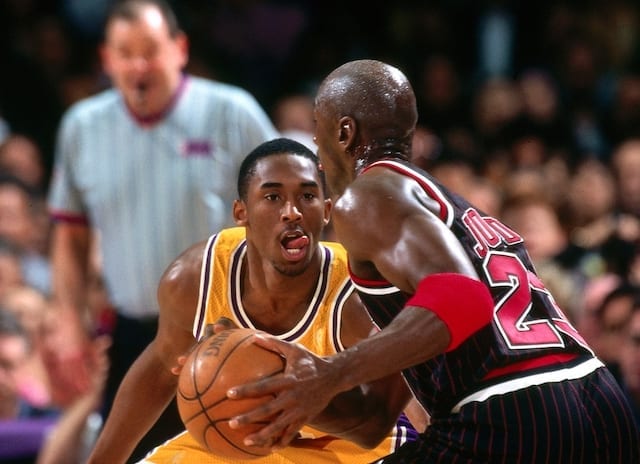

Leading up to the draft, Kobe had worked out for John Calipari, the newly-hired coach of the New Jersey Nets, on three separate occasions. Coach Cal loved Kobe and was eager to draft him with the 8th overall pick. It seemed like such an inevitability that Calipari and then-Nets general manager John Nash had dinner with Kobe’s parents the night before the draft. According to a 2011 story by ESPN New York’s Ian O’Connor, Kobe’s parents “were thrilled that their son would be playing within commuting distance of their suburban Philly home.”

On the day of the draft, with the Nets prepared to draft Kobe, everything changed. Kobe called Calipari and told him that he didn’t want to play for the Nets. Tellem called Nash and relayed the same message on behalf of his client. He even went so far as to threaten to have Kobe play in Italy if the Nets selected him.

Here’s what happened next, according to O’Connor:

Nash met with a panicked Calipari and tried to calm the coach. The GM made some phone calls and figured out that the Lakers’ Jerry West had reached an agreement with Charlotte, holding the 13th pick, to trade Vlade Divac for Bryant; West was confident that Kobe would make it to No. 13 if the Nets passed at No. 8.

Once Tellem and Adidas’ Sonny Vaccaro got wind of West’s interest, they decided they’d try to scare the Nets away from drafting him with those phone calls. But according to Nash, those phone calls had no bearing on the Nets eventual decision not to take Bryant. He insists that he knew Tellem was bluffing and that he still would have selected Kobe if that final decision was his and not Calipari’s.

Nash believes that what ultimately convinced Calipari to change his mind was a conversation he’d had with David Falk, who was not only the agent for Kerry Kittles but also repped Michael Jordan. Somehow during their telephone conversation, Falk convinced Calipari to draft his client instead of Kobe. As exec VP of basketball operations, the decision was Calipari’s to make and he didn’t want to make a huge mistake with his first big decision since being hired.

“Everybody knows I was talked out of that,” Calipari told Yahoo!, not specifying exactly who talked him out of it. Regardless, if he wanted to draft Kobe he could have. If he was talked out of it, that’s his fault.

Could you really blame Kobe’s reps from trying to get their client to the Lakers? The Nets had not only missed the playoffs in seven of the previous 10 seasons but hadn’t won a playoff series going back to 1984. On top of all that, Calipari was the franchise’s 12th different head coach in 16 seasons; not exactly the model for stability or the type of environment best-suited to nurture the development of a 17-year-old making the jump straight to the NBA. But that doesn’t mean that he wouldn’t have accepted it if it happened.

To this day, everyone on the Nets side still insists that it wouldn’t have prevented them from drafting Kobe if that’s what they’d ultimately decided to do. But that hasn’t stopped the masses from insisting that Kobe forced his way onto the Lakers by refusing to play for any other team.

After Kennedy’s initial tweet, I tweeted out Delong’s story that busted the myth of Kobe refusing to play for Charlotte. This prompted Matt Moore, blogger for CBSSports.com, to reply that DeLong’s story didn’t really bust anything. Moore was convinced that the Hornets executives were just trying to save their own hides, despite the fact that Bass is now 85 and has long been retired.

It seems as if Moore, like many others, will never be convinced otherwise. Never mind that Kobe worked out for the Nets three times or that his parents had dinner with their front office on the eve of the draft, never mind that Kobe worked out for the Celtics, who owned the 6th pick, or twice for the Clippers, who owned the 7th pick. I guess those were all smoke screens, right?

If you want to insist there was a conspiracy, I can’t stop you. But at least point your finger at the Nets and not the Hornets. The problem with blaming the Nets is that it would also dispel the notion that Kobe refused to play for a small market. If the conspiracy theorists accepted that the Hornets really did want Divac and that Calipari has no backbone, then they’d have nothing left to grasp onto. By insisting that Kobe refused to play for the Hornets, they can further strengthen their conspiracy with the bad team/small market combination. Kobe had canceled a workout with Sacramento and had declined the chance to work out for the Hornets.

Once he knew of the Laker’s interest, there was no reason to work out for the Kings, who owned the pick right after Charlotte or impressing the Hornets enough that they might change their minds about the Divac trade. If that meant telling Charlotte he didn’t want to play in a small market just to get past that last obstacle standing between him and the Lakers, then so be it.

There is one other theory out there that suggests that Kobe had intentionally maintained his amateur eligibility by not hiring an agent ahead of the draft. The story goes that by doing this, he could fend off undesirable teams by threatening to go to college if they drafted him. None of it is true. Not just the loophole, but the part about him not hiring an agent. Kobe had given up his amateur eligibility in May of 1996 when he signed his endorsement deal with Adidas. This is what Stephen A. Smith wrote in the Philadelphia Inquirer a month before the draft:

“Kobe Bryant has reached a multi-year agreement with Adidas to endorse footwear and apparel, officials said yesterday, erasing any doubts about the Lower Merion High star’s desire to bypass college and enter the NBA.”

My favorite part about that theory is that it has grown to include a part about Kobe’s parents using his father’s basketball-playing riches to pay for his travel expenses to workouts; as if to suggest that the only reason other prospects hadn’t used this strategy in the past was that none of them could afford to. At least that theory isn’t as lazy as the popular one, which is basically some variation of, “I don’t know exactly what happened, I just know that the Lakers cheated.”

If there is one thing people seem to forget most often, it’s just how risky the prospect of drafting a 17-year-old was back in 1996. There was no precedent for it. Before the draft, Selena Roberts of the New York Times described the idea of Calipari drafting Kobe as “an unpopular or risky choice.” She added, “His age alone, 17, leads most to believe he’s too young, too unknown and too much of a gamble to take in the top half of the draft.”

There are plenty of real reasons for people not to like Kobe Bryant. How he ended up on the Lakers just shouldn’t be one of those reasons.